How Scaffolding Learning Strategies Helps Your Child

January 16, 2020/ Shelah Moss / Parenting, Educational, Homeschooling, Special Needs, Autism / 0 comments

Scaffolding helps students to become independent self-regulating learners and problem solvers.

“When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, don’t adjust the goals, adjust the action steps.” -Confucius

Why should educators (and parents) use scaffolding learning strategies? Well, imagine that you are tasked with putting a piece of furniture together and when you dump out the parts and instructions you see parts that you don’t know the names of, the pictures are all fuzzy and the instructions are in a different language? Would you feel discouraged or overwhelmed? That’s exactly how many children feel when they are given a new task or skill to perform. Because they lack a foundation completing a complex assignment can feel like climbing Mount Everest. In order to encourage students to become confident and active learners we sometimes have to scaffold our lessons. This is also known as differentiated instruction and it is an important tool for parents and educators.

This page contains affiliate links. Please visit our disclosure page for more information.

The Definition of Scaffolding and “Zone of Proximal Development” and Differentiated Instruction

Scaffolding and ZPD are basically the same concept. The concept, zone of proximal development was developed by Soviet psychologist and social constructivist Lev Vygotsky (1896 – 1934).

The zone of proximal development (ZPD) has been defined as presented by:

“the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86).

The idea behind scaffolding is that with appropriate adult help, children can often perform tasks that they are incapable of completing on their own. With this in mind, scaffolding–where the adult continually adjusts the level of his or her help in response to the child’s level of performance–is an effective form of teaching. Scaffolding not only produces immediate results, but also instills the skills necessary for independent problem solving in the future.

Differentiated Instruction is when a teacher adjusts the way a lesson is presented based on a student’s learning style or abilities. It can also include modifying the environment to be more condusive for certain children, providing movement breaks or presenting the lesson with modified materials.

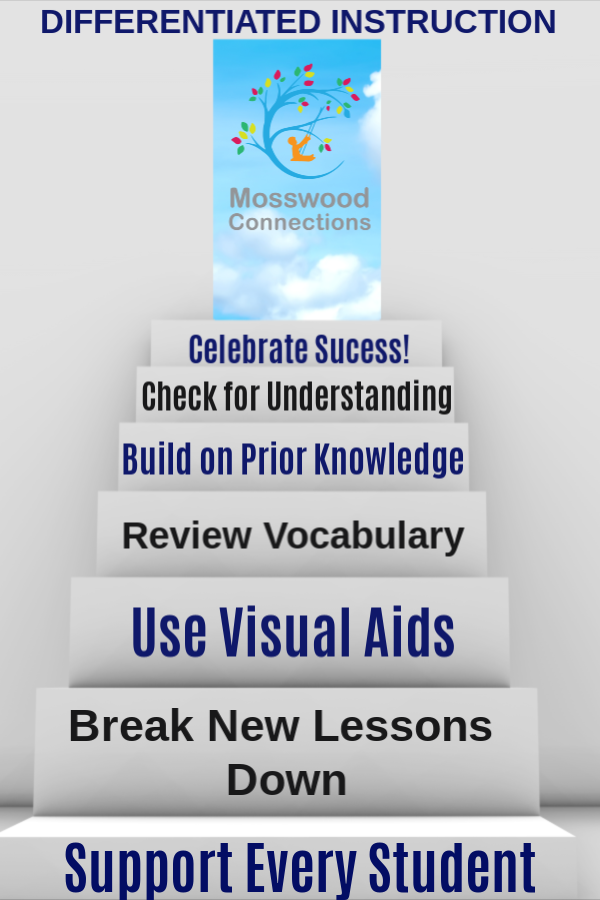

Whichever term you wish to use the basic idea is this:

- Create an environment that is condusive to learning.

- Present materials in a variety of ways to optimize a child’s learning style.

- Break lessons down into smaller steps.

- Provide materials that support the lesson.

- Give adult support as needed.

- Build on previously mastered skills.

Examples of Scaffolded Learning

We use scaffolded learning all the time in our work with children on the autism spectrum but it can be applied to any child and any type of skill building activity.

Example of Scaffolded Learning of Life Skills

The goal is to teach a child to put on a jacket and zip it up but the child does not have the skills to do this independently yet. First, you have the child practice putting on the jacket. Once the child has mastered taking their jacket off and on you introduce zippers to the child. This can be done with clothing or zipper practice toys. Once the child is able to successfully zip up the zipper toy, you have them practice zipping up a jacket on someone else (it’s a little easier) and finally the child practices the entire sequence on themselves.

Scaffolding Strategies for Communication

The examples for this can be endless; when working on speech goals one starts by asking the child to repeat sounds, then words, phrases and finally, complete sentences.

When we work with children who have A.S.D. we often need to scaffold our communication. For example, one child that we work with was having frequent tantrums whenever he wanted something. HIs default was to scream because he believed that no one understood what he wanted. One of the things that he wanted to do was to go into a linen cupboard, throw half the blankets on the floor, perch on top of the rest and close the door. (Maybe a strange example but that’s what he wanted.) If he was not allowed to do this he would have huge tantrums. This was not a desirable behavior…

I taught his parents to first model the language he should use: “You want to open the cupboard and go inside to lay on the blankets.” With practice he gained the ability to say, “Open cupboard” and “blanket” and “Close door”. This way even though we weren’t thrilled with the behavior we were at least getting language out of him.

Then we validate that we understand, “I understand that you want to open the cupboard and go inside,” and we allow him to go inside the cupboard. (This is when his parents started to question my methods.)

Finally, once he masters communicating his desire and he demonstrates that he understands our response it’s time to modify his behavior. Now when he asks to open the cupboard so he can hide in comfort I say, “I understand you want to open door. I understand that you want to go inside. I want the doors to stay shut.” (I had a fun back in forth with him – “Open door”, “Door stays shut”, and on and on but no tantrums). Then I offer a high interest alternative activity to refocus his attention. In this case, it was doing an art project from Easy Paper Projects book.

By scaffolding the steps of communication the tantrums diminished and ultimately stopped and his parents became believers in my methodology. The same steps were effective for this child with other situations such as wanting to stay in bed instead of going to school.

Examples of Instructional Scaffolding

We use instructional scaffolding when homeschooling and with our students who have learning disabilities.

- Tap into prior knowledge. Ask students to share their own experiences and ideas about the content or concept of study and have them relate and connect it to their own lives.

- Break down lessons into smaller steps.

- Identify a student’s learning style.

- Present materials that match different learning styles: visual materials for visual learners, audio books for auditory learners, hands-on materials for kinesthetic learners, etc.

- Pre-teach parts of the lesson such as reviewing vocabulary.

- Model thought process and appropriate actions.

- Check for understanding, pause, ask questions.

- Provide support materials such as graphic organizers.

For example, you want a student to produce a five paragraph essay, you will first need to ensure that the student has prior knowledge on how to write a paragraph. If the child can produce a decent paragraph you can move forward. If not, writing paragraphs will need to be taught first. Talk about the writing assignment, discuss possible topics and supporting details. Ask questions to make sure the student shows that they understand. Provide the students with writing support materials. These could include story webs, mind maps, or writing outlines. Support the student in filling out the support material and check for understanding. Have the student write one paragraph at a time and once they are all complete put them together. You can stop there if that was enough for that student’s skill level or you can move on to editing. Provide an editing checklist or go over one skill at a time together. Have them edit for puncuation then capitalization, etc. Once the steps are done the student should have a finished work product.

The next step is to start slowly fading adult support until the student can accomplish the task on their own. This process can be time consuming but it’s worth spending the time to ensure that the student is acquiring the skills they need to work independently.

Tags EducationSpecial Needsautismscaffoldingteachingdifferentiated instruction